Trudeau is failing to meet his own government transparency standards

This piece was first published in the Telegraph-Journal.

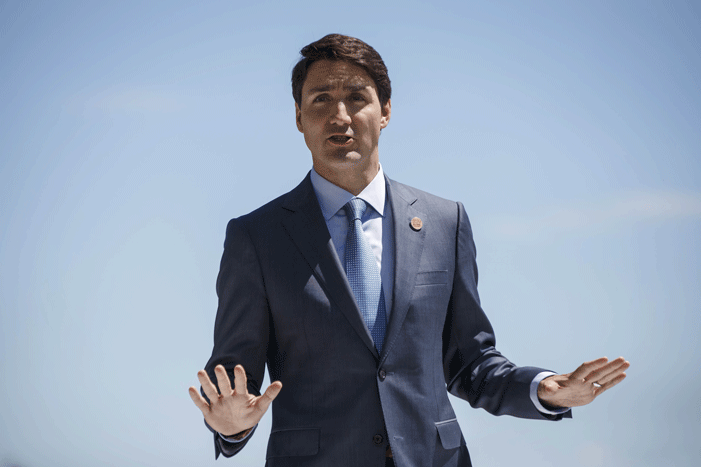

Transparency seems to be a moving target for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his government. Back in 2015, the prime minister won on a platform of “openness by default.”

Five years later, and the best we can get is Trudeau’s affirmation that he and his government were trying to hit a balance between transparency and a level of secrecy where the government could cover its metaphorical backside.

Setting aside the rather paternalistic notion that our elected representatives need to keep us in the dark, it’s clear our current access to information laws have erred much further on the side of backside-covering secrecy rather than transparency and openness.

The Halifax-based Centre for Law and Democracy has partnered with the European think tank Access Info to provide a comprehensive analysis of right to information legislations all around the world. The Canadian government provides funding for the project.

In its latest edition, Canada’s Access to Information Act ranks 50th out of 128, behind stalwarts of transparency such as Russia (43rd), Pakistan (32nd) and South Sudan (12th). That’s hardly a spot we want to find ourselves in given just how important a strong right to information is when it comes to holding our leaders accountable.

And while our overall score did get better over the years, we haven’t kept pace with the increase in transparency internationally as we now sit seven ranks below where we sat when those rankings were first compiled nine years ago.

While few readers may use their right to access government information, it’s important to note that this principle has a direct impact on our lives. As Brent Jolly of the Canadian Association of Journalists put it: “Freedom of information requests are a critical tool for journalists to do their job effectively and to hold governments, of all political stripes, to accounts.”

These requests allow citizens, advocates and journalists to shed light on examples of government corruption, abuse of power or outright waste, thus helping make the case for changes. They are essential to a healthy democracy.

Unfortunately, as those who have used these requests in the past will tell you, it’s a constant battle to get even the most basic information. There are ludicrously long delays beyond the legislated 30-day timeline, often reaching months, and, in one case, 80 years. There are exemptions so broad that nearly anything falls under them.

Take the 20-year ban on disclosing cabinet confidences for instance. Previous Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault told MPs in 2016 the exemption was overly broad and recommended background information documents and analyses of problems prepared for cabinet be exempt from cabinet confidence as they are purely factual documents and do not contain ministers’ opinions and deliberations. Four years later and even this small, reasonable fix has yet to be implemented.

Or take the Centre for Law and Democracy’s proposal to subject all existing exemptions to a public interest override. Most Access to Information Act exemptions have no public interest clause allowing for their override which means information is kept secret even when there’s a compelling reason Canadians should know about it.

So while we’d certainly prefer to see Trudeau honour his previous commitment of “openness by default,” even reaching that supposed balance between transparency and government backside-covering would be welcome at this point. As it stands, we’re nowhere close to reaching it.